What is a code block ?

A code block is a piece of Python code executed as a unit:

- A function body is executed as a unit

- A script file to be run from the terminal using Python shell:

python ./script.py - A module is a unit

- A class definition is a unit

- A single command run in a python interpreter is a unit

we already saw what are names/variables = pointers refering to an object location, hence being bound to it doing so.

You can then adress the object by using its associated name.

But is any binding created within a block still visible anywhere in the code?

By "visible" we not only mean nameA exists, but that the relation to the object objectA is still valid.

The "where" the bindings, defined in a block, are "visible/meaningful", is also named scope of a name/variable.

scopes are determined statically, they are used dynamically

Sometimes, scope is also defined as the set of variables/names available at a certain point in the code, but this refers more to the context of namespaces.

but it is better to take the definition of W3Schools:

A variable is only available from inside the region it is created. This is called scope.

scope

# variable defined in a block

a = 4

# in the same block, `a` is visible

print(a)

4

# a is defined on the block module level

# ...(imagining this markdown code is a .py file on its own)

# a is then a global variable (RELATIVE to this module)

a = 4

# a is then reachable for any block within this one, which is the top-level

def multiply_by_2():

# the function body is a block

# b is bound to the object of value 2 within that block

# b is then said a "local variable"

b = 2

# it is discoverable anywhere after this assignement

# and inside any inner blocks may exist

# a is not defined, but was in the nearest enclosing scope

# in a function, as highlighted in the FAQ, referenced variable are implicitly global

return a*b

multiply_by_2()

8

If we change a little bit the code to that, it will raise us an UnboundLocalError:

a = 4

def multiply_by_2():

print(a)

a+=1

b = 2

return a*b

multiply_by_2()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

UnboundLocalError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-96-98e4dc25cb3c> in <module>

7 return a*b

8

----> 9 multiply_by_2()

<ipython-input-96-98e4dc25cb3c> in multiply_by_2()

2

3 def multiply_by_2():

----> 4 print(a)

5 a+=1

6 b = 2

UnboundLocalError: local variable 'a' referenced before assignment

It has a pretty good explanation on the Python FAQ. If you make an assignement in the function scope,

abecomes a local-variable to that function block and **shadows** any same named variable in the outer/enclosing scope. “The compiler recognizes this as a local-variable. Hence any statement before the variable has actually been assigned raise an UnboundLocalError.

Same explanation in different words from the docs: “If a name binding operation occurs anywhere within a code block all uses of the name within the block are treated as references to the current block. This rule is subtle. Python lacks declarations. The local variables of a code block can be determined by scanning the entire text of the block for name binding operations”

If you recall the course from the functional programming, it is the same type of behavior when any yield word scanned within the function body makes it a generator

To workaround this issue, we can use global keyword, saying “no, this is not a local variable, use the global variable a that must have been defined elsewhere, at top-level module.

a = 4

print(id(a))

def multiply_by_2():

global a

print(id(a), a) # same object location

a+=1

print(id(a), a) # different because it is an immutable

b = 2

return a*b

BERTIN

multiply_by_2()

4465474080

4465474080 4

4465474112 5

10

if the name is not found in the function body or enclosing scopes, you get a NameError exception

a = 4

Luc BERTIN

def multiply_by_2():

return a*c

multiply_by_2()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-39-64522ae2309b> in <module>

----> 1 multiply_by_2()

<ipython-input-36-9910d1b69fd6> in multiply_by_2()

2

3 def multiply_by_2():

----> 4 return a*c

NameError: name 'c' is not defined

Namespaces

Python needs to keep track of all the ‘visible’ bindings within a block, or at a certain point of the program, this is also called namespace or context.

{

symbolic_name1 : referenced object1,

symbolic_name2 : referenced object2

}

Namespaces are implemented as dictionaries in Python, a table listing symbolic variables/names (keys) to their objects (values) at a certain point in the program.

back to the definition of scope we can pick up from the [docs]:(https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/classes.html)

A scope is a textual region of a Python program where a namespace is directly accessible.

globals() is a built-in function which returns the global namespace/context

globals()['a']BERTIN

4

You can use it to change a globally defined binding

globals()['a'] = 37

print(a)

37

locals()is a built-in function which returns the local namespace

in the top-level module, locals and globals return the same thing

locals() is globals()

True

but inside a function it is not,

def function():

a = 2

print( "Is locals() same as globals()? {}".format(locals() is globals()))

print( "Locals dictionary: {}".format(locals()))

print( "What about name a in globals(): {}".format({k:v for k,v in globals().items() if k=='a'}))

function(Luc BERTIN)

Is locals() same as globals()? False

Locals dictionary: {'a': 2}

What about name a in globals(): {'a': 37}

note: after the function finishes executing, Python “forget” about the function local namespace

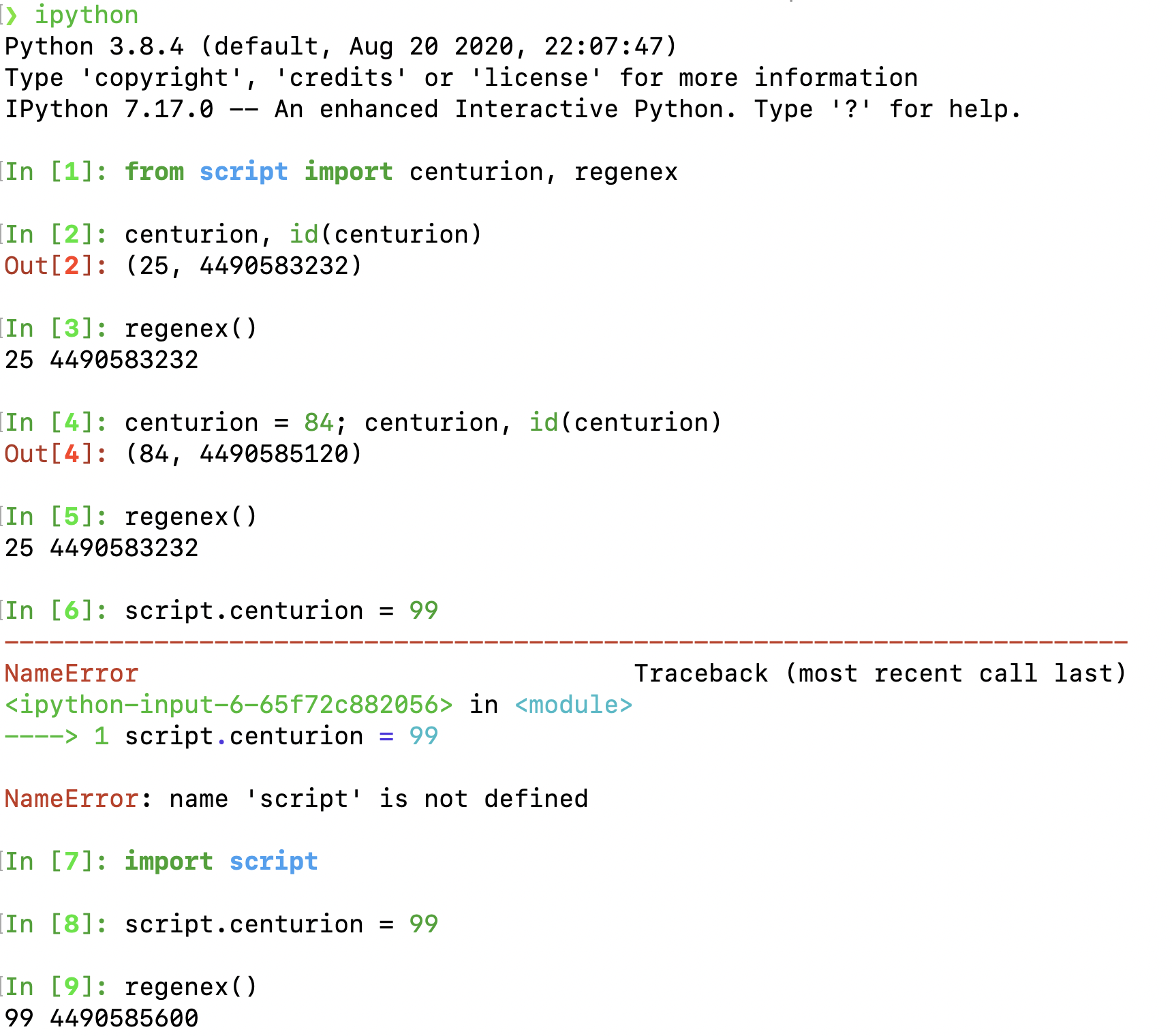

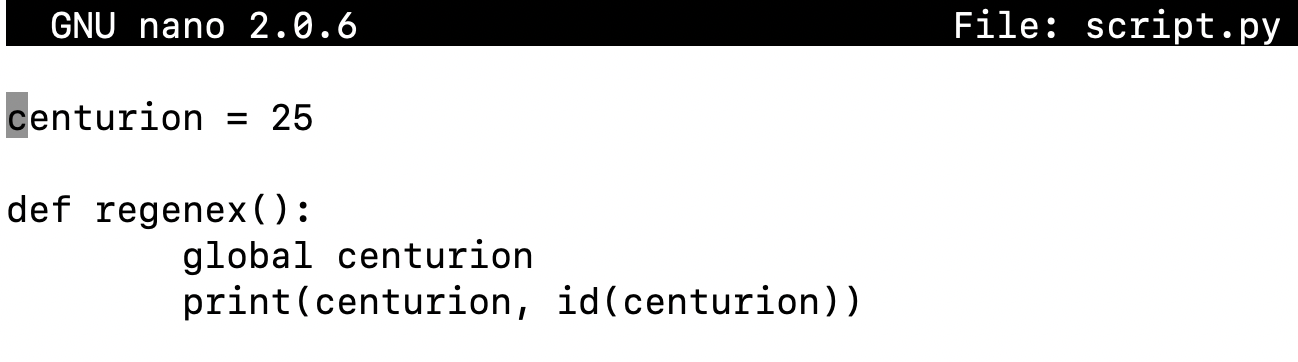

**Caution:** global variables are relative to a module context/namespace

they are not shared across all modules.

All the global variables i wrote since then can also be seen in __main__ (name of the scope in which top-level code executes)

import __main__

__main__.aLuc BERTIN

37

This is a working example attached here

The local variables are always the ones defined within the current called function

a

37

def function():

print("outer function locals:{}".format(locals()))

d=4

def function2():

b=2

print("inner function locals:{}".format(locals()))

nonlocal d

c=3

print("outer function locals:{}".format(locals()))

function2()

print("outer function locals:{}".format(locals()))

function()

outer function locals:{}

outer function locals:{'function2': <function function.<locals>.function2 at 0x10e39bca0>, 'c': 3, 'd': 4}

inner function locals:{'b': 2, 'd': 4}

outer function locals:{'function2': <function function.<locals>.function2 at 0x10e39bca0>, 'c': 3, 'd': 4}

def function():

def function2():

nonlocal c

c += 4

c=3

print("outer function locals:{}".format(locals()))

function2()

print("outer function locals:{}".format(locals()))

function()

outer function locals:{'function2': <function function.<locals>.function2 at 0x10e39bdc0>, 'c': 3}

outer function locals:{'function2': <function function.<locals>.function2 at 0x10e39bdc0>, 'c': 7}

3 types of namespace exist:

- Built-in namespace: containing the built-in objects (

dir(__builtins__)to list them) - Global namespace: global names IN THE MODULE

- Local namespace

There is absolutely no relation between 2 names in different scopes.

Each module has its own private symbol table, which is used as the global symbol table by all functions defined in the module.

The statements executed by the top-level invocation of the interpreter, either read from a script file or interactively, are considered part of a module called

__main__

names are resolved dynamically at runtime by following the LEGB rule:

- is the variable Local?

- no? is it in the nearest Enclosing blocks?

- no? may be Global to the module ?

- then look in Built-in namespace or raise an exception

Classes

classes have their own namespace

In a sense the set of attributes of an object also form a namespace

obj.name is an attribute reference, a name in obj namespace bound to a corresponding method or attribute

class Test:

i=12

globals()['Test']

__main__.Test

module import

import webencodings

globals()['webencodings']

<module 'webencodings' from '/Users/lucbertin/.pyenv/versions/3.8.4/lib/python3.8/site-packages/webencodings/__init__.py'>

del webencodings

from webencodings import ascii_lower

globals()['webencodings']

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-237-3cf7b0abaaac> in <module>

----> 1 globals()['webencodings']

KeyError: 'webencodings'

globals()['ascii_lower']

<function webencodings.ascii_lower(string)>

One word on mutability

multiple names (in multiple scopes) can be bound to the same object. This is known as aliasing. Passing an object as parameter to a function is cheap since just a pointer is passed by the implemententation. Hence using mutable objects might affect the code

Beginning in Python

Beginning in Python