You’ve probably heard of list comprehension in Python before. It is a declarative-like, concise, and generally easier way to read than a simple for loop.

Example:

[x ** 2 for x in [0,1,2]]

Have you also heard of generator expression in Python?

(x ** 2 for x in [0,1,2])

Reduced to appearance, the only notable difference would be the removal of brackets for the addition of parentheses? But is this really the case in practice?

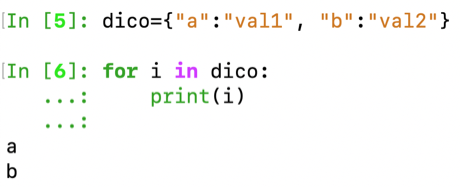

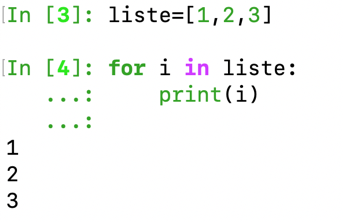

Have you noticed that you can easily iterate over a list, dictionary, tuple, or string with a for loop? What are the shared similarities among all of these built-in types ?

Why functional programming ?

Picking up the definition from the python docs: functional programming is the principle of breaking down a problem into a set of functions which take inputs and produce outputs. They have no internal states subject to altering the output produced for a given input, and act deterministically for some given conditions. We can therefore in a certain way oppose functional programming to object-oriented programming in which an instance of a class can see its internal state, represented by its attributes, be modified internally by the call of associated methods.

Thanks to this definition we can already understand the assets of functional programming. First by its modularity: each function would fulfill a precise, well-defined task and we could therefore break down a large problem into several mini-problems in the form of functions.

Then each function would be easy to test (by that I mean develop an associated unit-test) due to its reduced action spectrum and its deterministic side.

In a data scientist approach, this approach would allow us to build pipelines, in which some flow of data would pass through different processing functions, the output of one would be the input for another, and so on.

Another big advantage is the parallelization: as each function is stateless and deterministic i.e. f(x)=y, if we wish to transform a sequence of elements, we can transform parallely each element x1, x2, x3,… of this sequence into y1, y2, y3,… by calling f in parallel for each input

Here, of course, I show a fairly simplistic but totally viable diagram, for example transforming the column of a dataset into a log.

1. the iterators

definition

Again, based on the official python documentation: an Iterator is an object representing a sequence of data. The object returns data one item at a time, much like a bookmark in a book announces the page of that book. It is an object that enables to traverse a container, such as list or dict.

To know if we are dealing with an iterator we must look in the magic methods associated with this object: if the object contains the __next__() and __iter__() methods then it is an iterator. This is also called the iterator protocol.

This method can also be called by the function: next(iterator) and simply allows you to return the next element of the sequence, as by moving the bookmark of the book.

If the last element is reached and __next__() is called again, a StopIteration exception is raised.

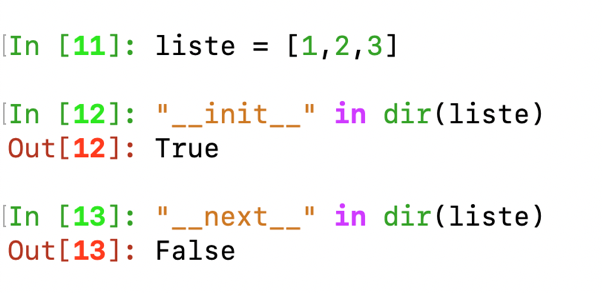

A list is a sequence of elements, is a list an iterator?

We can call dir(), a built-in function that returns a list of attributes and methods (magic or not) for a given object.

We can see that __next__ does not exist here. List is therefore not an iterator.

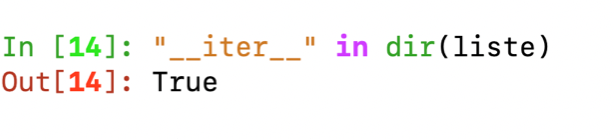

On the other hand, we see that the __iter__() method exists:

This method can also be invoked from the iter(list) function.

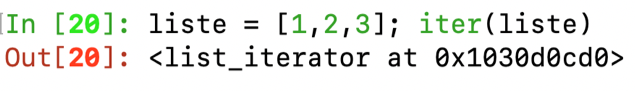

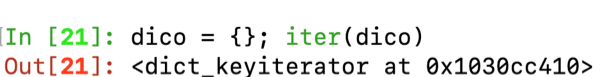

What does iter() produce from this list?

Iter seems to return an iterator from the list.

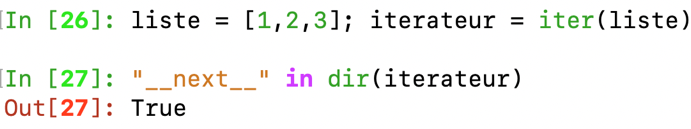

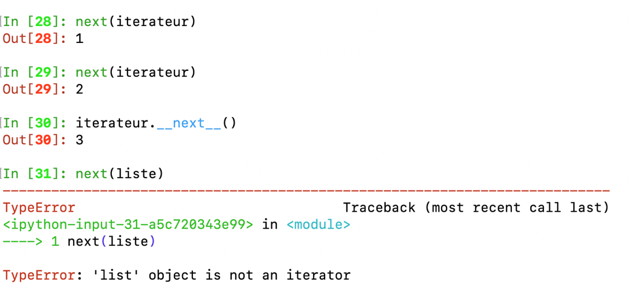

We can verify it as follows:

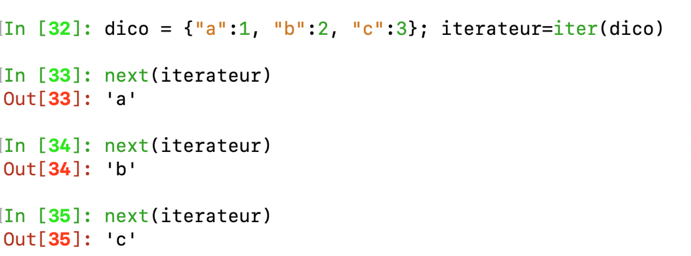

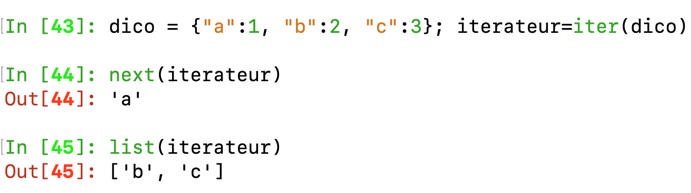

If we do the same thing on a dictionary, this is what we get.

Again an iterator.

Now, we can return each of the elements sequentially by calling next().

Conversely, we can also call iterator.__next__()

Note again that next(a_list) cannot be done, the error message is self-explanatory.

Thus we see that a dictionary or a list, although being a sequence of objects, are not iterators, but iterables, that is to say that we can create an iterator from those - here by calling the __iter__ method, the iterator being, I remind you, is an object, which returns its elements one by one thanks to the implementation of its __next__ method.

In a similar fashion, we can therefore consider the book as an iterable, i.e. a sequence of elements from which we can create an object that returns each of its pages one by one.

We also see that only the dictionary keys are returned here. (Reminder, if we want to return tuples of (key, value) we can use the items () method in python 3+).

Isn’t this behavior similar to what you would get by looping with for?

This is what is implicitly done when looping through a dictionary or a list: As the python documentation shows, these 2 loops are equivalent.

for i in iter(obj):

print(i)

for i in obj:

print(i)

So that’s what’s behind it when you loop through a sequence of tuple, list, or dictionary elements. Note that we can also express an iterator as a list or tuple from the constructor of these objects which can admit an iterator as a parameter.

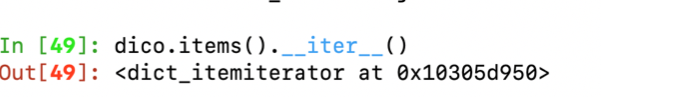

To get the original dictionary from the old example again we can also call the dict() constructor on the previously discussed item_iterator.

If we can extract an iterator from an iterable, and iterate over it, what’s the point of this extra step, why doesn’t list understand the __next__ method?

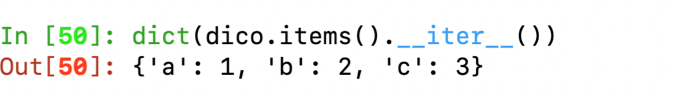

Well because an iterator can only be iterated once, once “consumed” it is necessary to recreate a new iterator from the iterable. The idea is that a new iterator will start at the beginning, while a partially used iterator picks up where it left off.

Wikipedia defines it well: you must see an iterator as an object that enables a programmer to traverse a container and gives access to data elements from this container.

This iterator could use data stored in memory (from a list by iterating on it), or read a file or generate each value “on-the-fly”.

Creating an iterator

Here is a Counter class which defines an iterator, here the values are generated on-the-fly rather than stored previously in a list. You are probably starting to understand now the crucial functionality that some iterators bring, if you do not need to store all the values in memory, where in the case of infinite sequence, you can successively generate the values and do calculations on these at the time of iteration / “lazy generation” which results in less memory usage.

Some iterable are lazy too, it’s the case of map objects.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

class Counter:

def __init__(self, low, high):

self.current = low - 1

self.high = high

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

self.current += 1

if self.current < self.high:

return self.current

raise StopIteration

for c in Counter(3, 9):

print(c)

3

4

5

6

7

8

Note: iterators implement __iter__ method just as iterables, they just return themselves (return self), they can then be used in for-loops just the same way iterables did.

A nice use-case

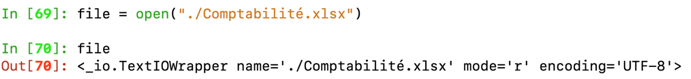

Opening a file using the built-in open() function generates a file object which turns out to be an iterator! Reading line by line using a for loop implicitly calls the readline method, so only certain lines can be re-requisitioned on demand, rather than reading the whole file in memory, particularly useful in the event of a large file!

We can therefore only traverse the file once (unless we reopen and recreate another iterator), and can just load the lines on demand that we want!

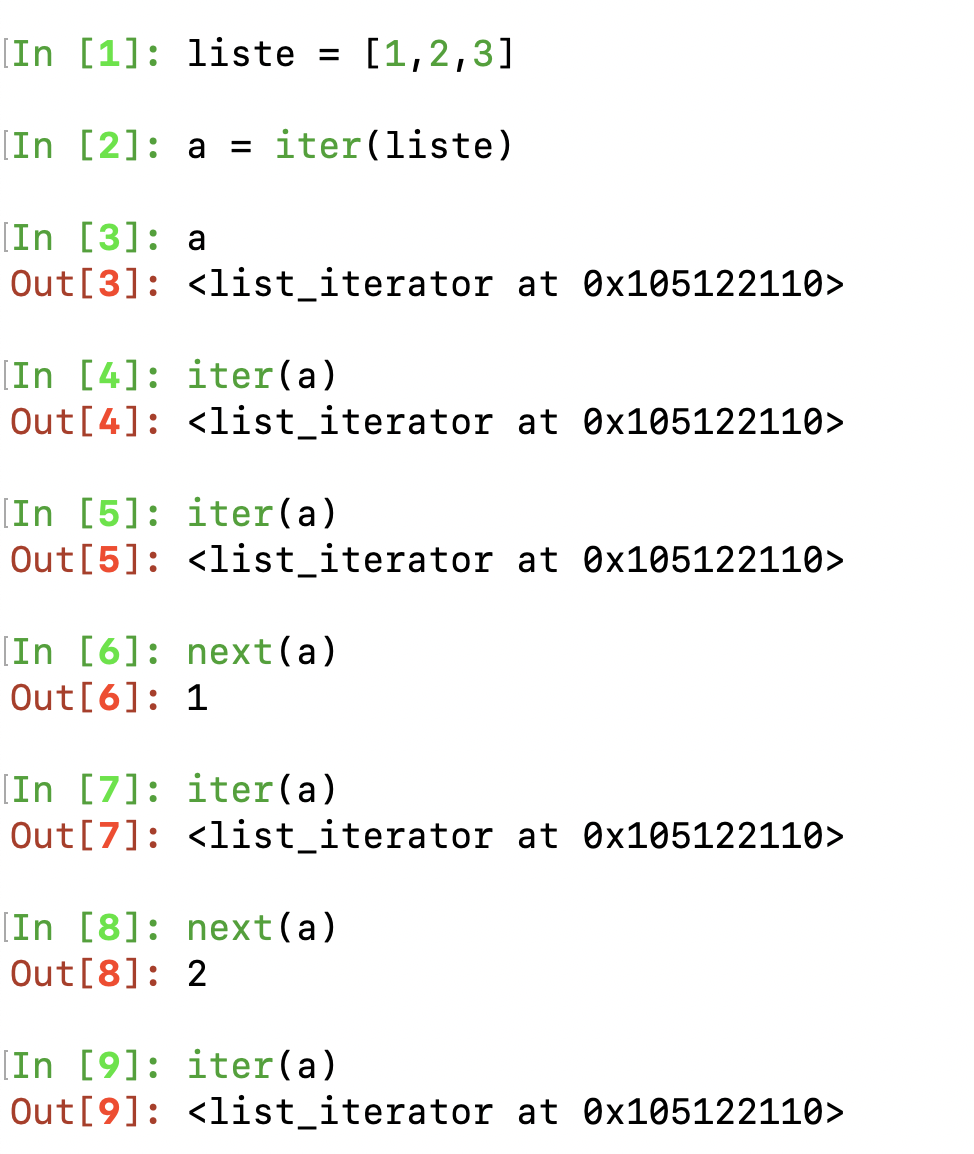

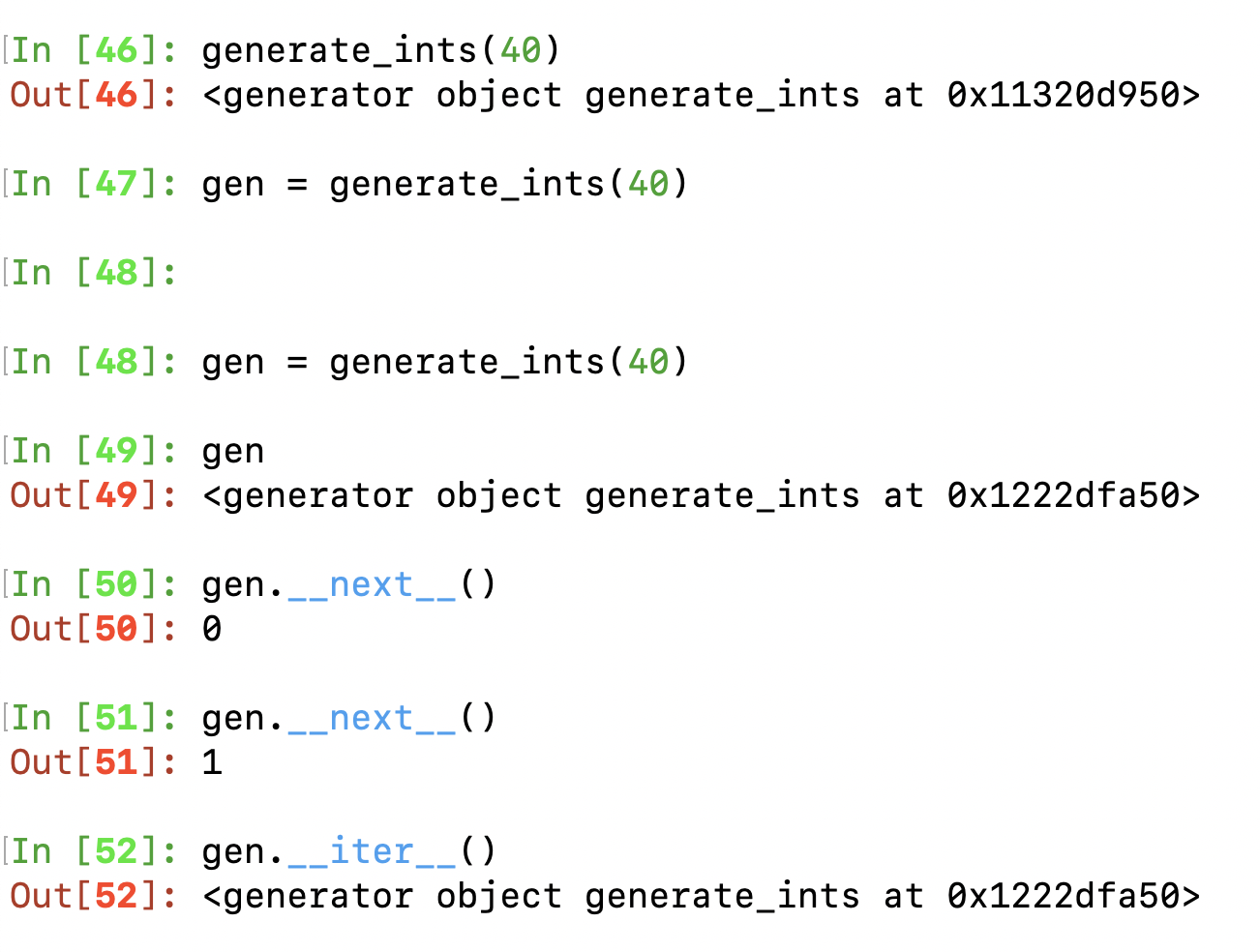

Something interesting to mention, calling __iter__ on a iterable such as a list returns a new iterator each time (reading the beginning of this article should help you understand why). However, doing the same thing on an iterator returns himself. Have a look at the below screenshot and then look back at the Counter class definition.

2. The generators

Generators vs Iterators

Don’t get me wrong, generators are not something different from an iterator, they are actually iterators. Conversely, iterators are not all generators.

Why are generators objects… iterators? because they implement __next__

and __iter__ methods.

How to create a generator object? from a generator function or a generator expression.

What are the purpose of doing so? writing a generator function (or a generator) expression is generally being easier to write than iterators (where we created a class and implemented by hand the 2 magic methods). Here we will implement some sort of logic in a function or an expression. When called they will return a generator object which behave the same way as the iterator i’ve mentionned.

I will then break this section in 2 parts: generators expression and generators ‘functions’, as they share similarities in their implementation.

Generators expressions:

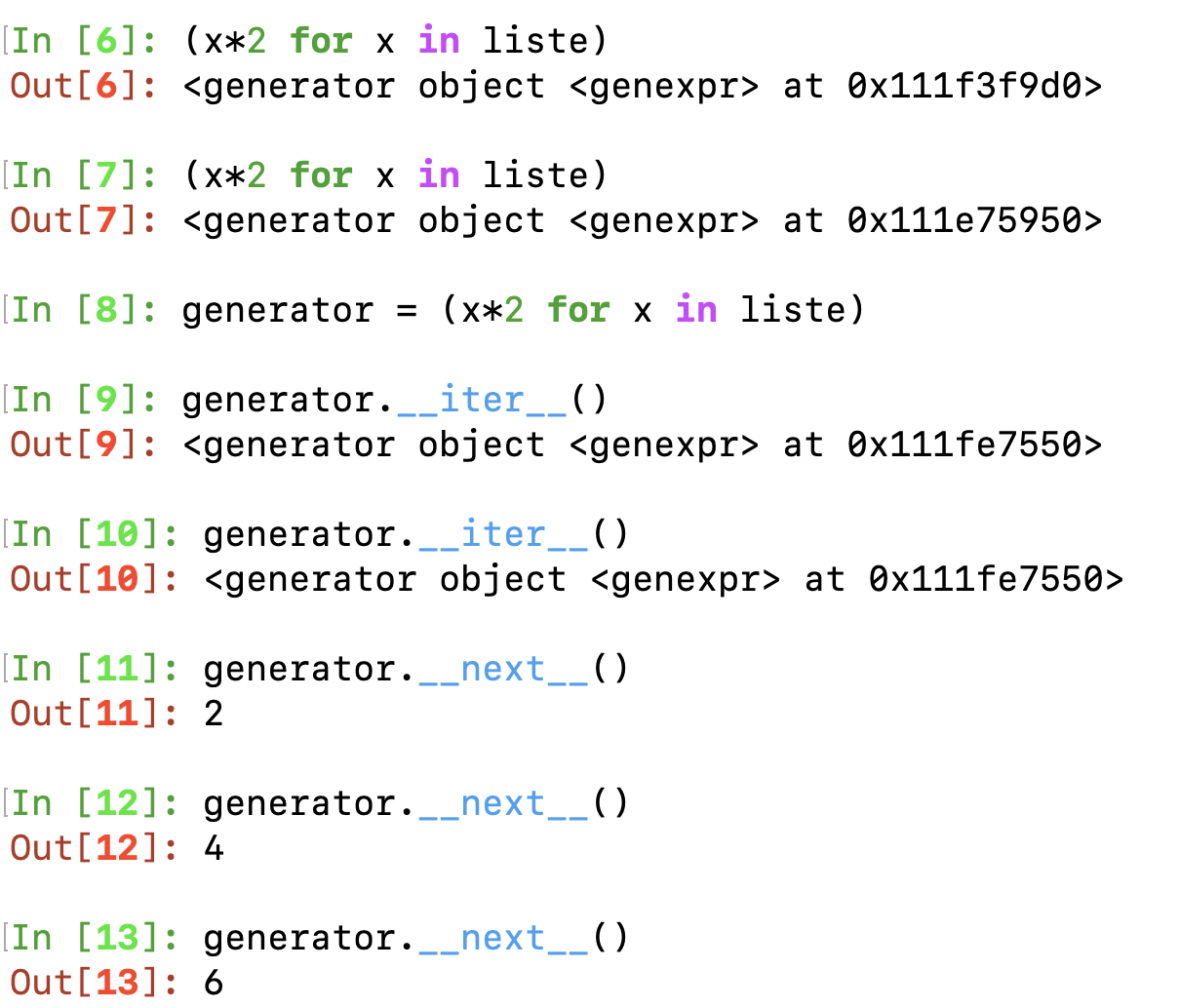

Back to the first paragraphe of this chapter, we talked about list comprehension and generator expression.

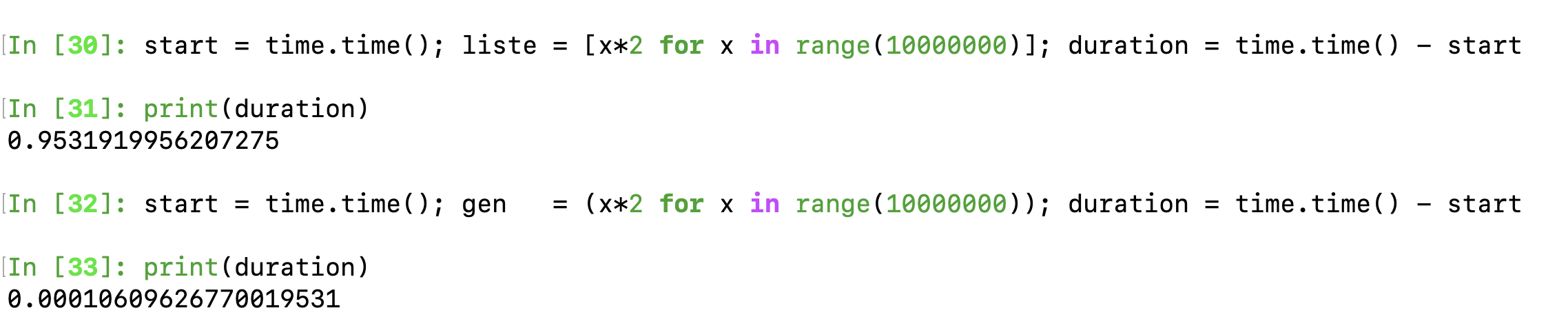

Here you can see the object returned behaves exactly as an iterator. It is indeed an iterator. But, once again, why not using simply list comprehension rather than generator expression? because of memory usage and lazyness evaluation of each item. When we use a list comprehension, every element of the list have been computed and the whole result is returned as a list with allocated memory space.

When we use a gen expression, elements of the sequence are evaluated only when requested (lazy evaluation). This lead to use less memory and sometimes, depending on what you do thereafter, an increase in performance.

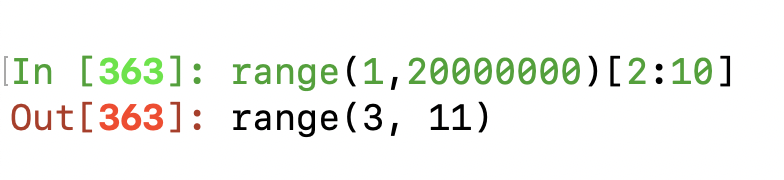

Note that range(start, stop[, step]) here is actually an iterable. It does not implement __next__ unless you call iter() on it. However, range implement lazyness implementation, just like previously showed iterators, it will always take the same (small) amount of memory, no matter the size of the range it represents (as it only stores the start, stop and step values, calculating individual items and subranges as needed). Also range has the nice property to be indexable, which is not the case of our simple generator expression.

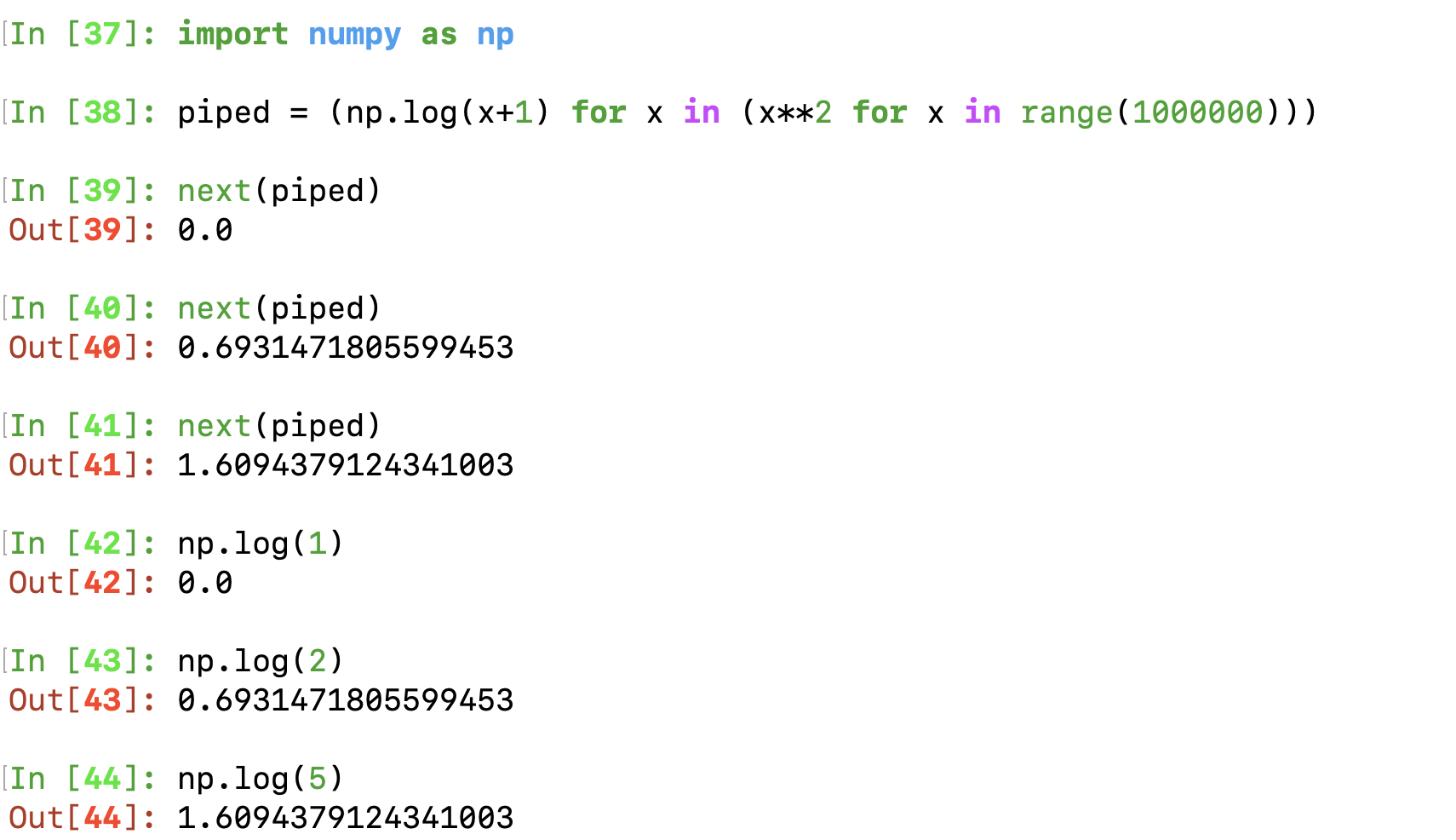

I can then start doing fancy stuff such as piping generator expression:

Here is a code to make an generator indexable, seems beautiful. Have to test it .

Generators functions:

Have you ever seen the yield keyword in certain functions before ? That keyword tranforms the function definition into a special type of function — when compiled into Bytecode —, named generator functions, also abbrieved generators.

Instead of destroying local variables defined in the scope of a normal function when this function returns a value or ends, you can here resume the function where it left-off, preserving those local variables.

Test those lines of code from the documentation and see the behavior of the function.

1

2

3

def generate_ints(N):

for i in range(N):

yield i

The generator function, when called, returns a generator object, which is an iterator, which implements next and iter and controls the execution of the generator function. Close behavior to a generator expression here. Hence the close names. yield operates just like a return statement then, but preserved the state of the local variables for later ‘next’ calls.

As you can also see, the above function is easier to write than Counter although achieving the same thing at last.

sending values to a generator function

As highlighted by the Python docs, you can also send values to the generator by writing: val = (yield i). Actually, the value of the yield expression after resuming the function is None if __next__() has been used. Otherwise, if send() was used, then the result will be the value passed in to that method.

Have a look at the counter definition from the docs:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

def counter(maximum):

i = 0

while i < maximum:

val = (yield i)

# If value provided, change counter

if val is not None:

i = val

else:

i += 1

and the output where you can send an arbitrary value inside of the

>>> it = counter(10)

>>> next(it)

0

>>> next(it)

1

>>> it.send(8)

8

>>> next(it)

9

>>> next(it)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "t.py", line 15, in <module>

it.next()

StopIteration

hence, yield does not only preserve local variable but gives us an entrypoint to the generator function to send input.

3. Functions operating on iterators

Now that you have a good grasp on how to design one-time objects that read through a sequence of elements, it is to browse some built-in Python functions that leverage use of iterators.

any() and all()

Clearly the first ones that come up to my mind: those functions are evaluating trueness of elements of a sequence.

- any return True if any element of a sequence is true (caution: 0 and None are falsy)

- all return True is all element of a sequence evaluates to true. But the most interesting about those 2 functions is that they are lazy, this means, they abort as soon as the outcome is clear. Combined to a generator expression, this could drastically improve performance rather than using a list-comprehension (hence resulting in returning a complete list first before evaluating trueness of the elements)

Don’t do that:

all([x for x in range(0,100000000)])

But that:

all((x for x in range(0,100000000)))

compare the difference in execution time, why do the second one stop so quickly ? (reminder: 0 is falsy)

By the way, you can delete the parentheses when the generator expression is used directly in a function that can expect to take iterators as parameter.

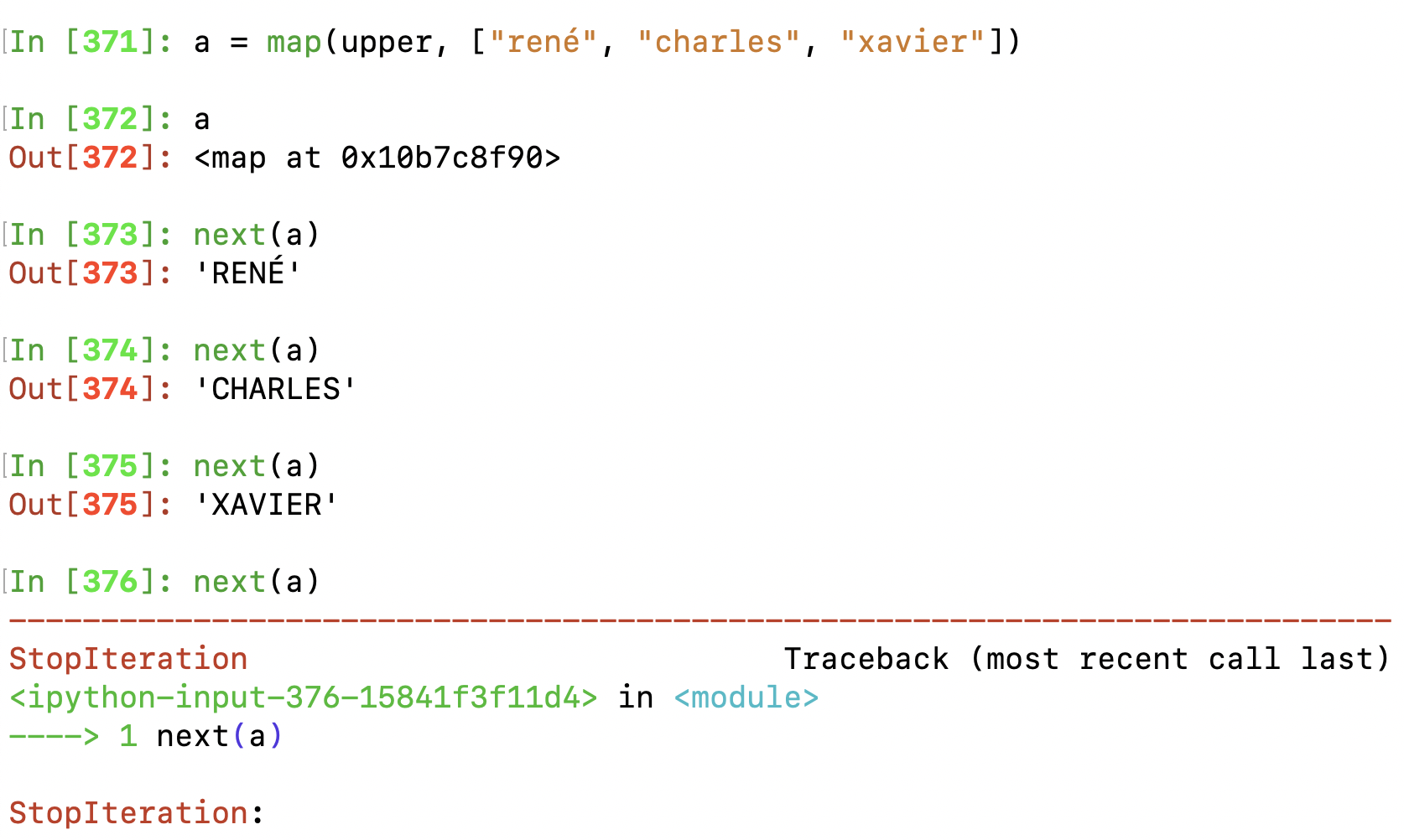

map(function, sequence(s)) (imap in Python 2+)

In Python 2 (deprecated as of 2020), imap is the lazy version of map. In Python 3+, map replaced imap. Thus as of Python3+, just use only map. map returns a map object an iterator and evaluates an iterator as parameter lazily evaluated.

Interesting sidenote i didn’t know before reading the docs, you can use map with 2 or more iterators and encapsulate them in the lambda x1,x2,x3,… function.

filter(function, sequence)

Also returns an iterator, whose content has been filtered from another sequence.

- 1st parameter: a function to evaluate trueness, if

None: return only non-falsy elements from the sequence - 2nd parameter: iterable evaluation

Note that filter(function, iterable) is equivalent to the generator expression (item for item in iterable if function(item)) if function is not None and (item for item in iterable if item) if function is None.

filter(None, range(0,10000000000000000000))

Very fast isn’t it? once again, the iterator returned is evaluated only on demand when calling __next__

The itertools module

The Python docs also mention the itertools module that add some other functions making use of (or returning) iterators, i will just then pick the one that i found quite important:

- itertools.count(start, step) => returns an infinite stream of evenly spaced values.

- itertools.cycle(iterable) => from an iterable, returns an infinite stream of copies of this iterable

- itertools.repeat(elem, [n]) => similar to iterable, but with an element only, repeated infinitely or n times

- itertools.chain(iterA, iterB, …) => concatenates the iterables

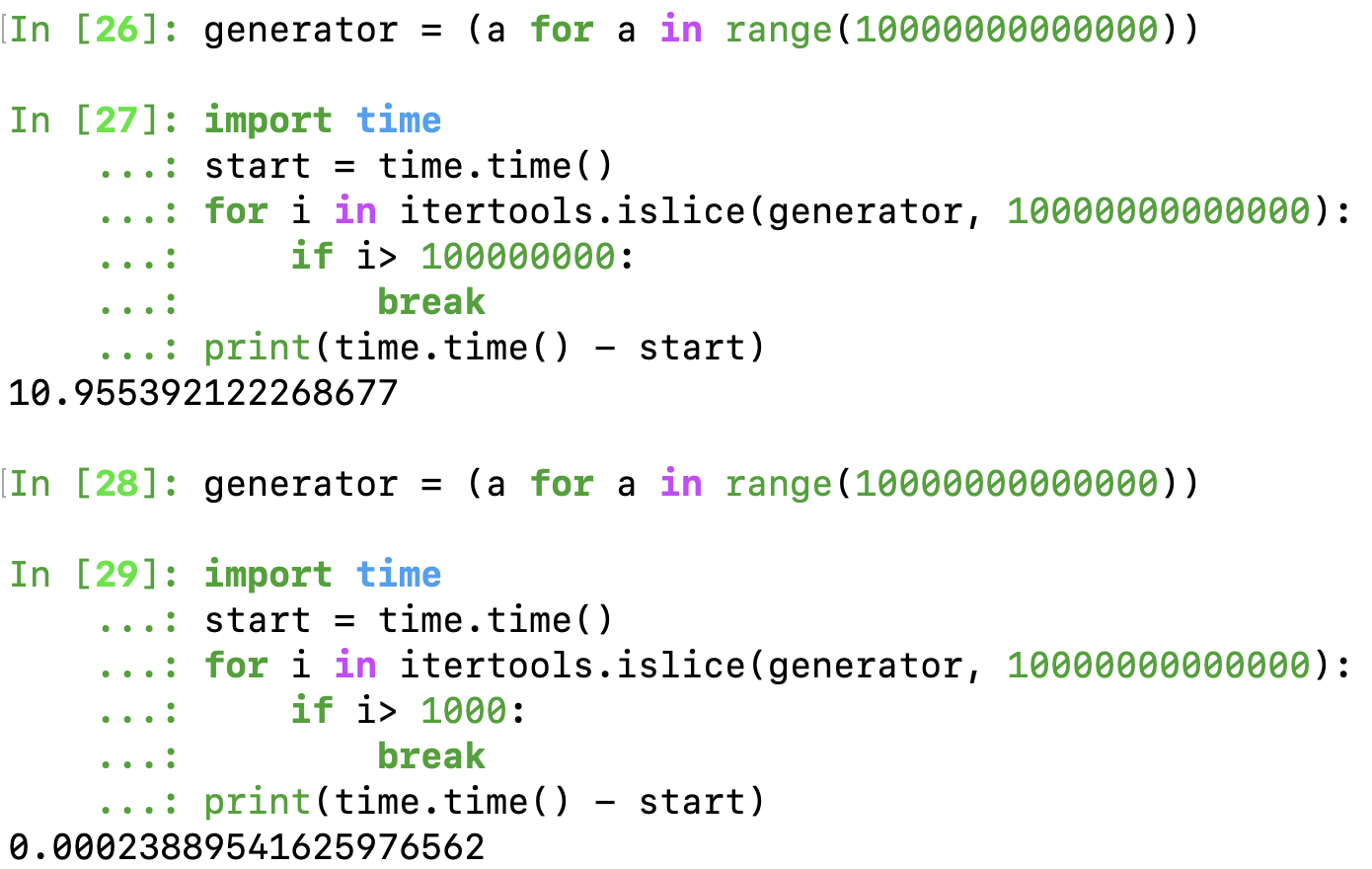

- itertools.islice(iterable, [start], stop, [step]) => from an iterable, return a slice of it.

- itertools.tee(iter, [n]) => copy n times the provided iterator (reminder: once consumed, an iterator cannot be used anymore)

- itertools.starmap(function, iterable) => the name is actually well chosen, think of it as a

*mapor maybe more likemap(function, *sequence_of_tuples). For sequences being tuples: it will unpack each tuple and apply the function with multiple unpacked paramaters f(*tuple) - itertools.takewhile(predicate, iter): returned an iterator sliced from the iterable till the first falsy value from the predicate is encountered.

- itertools.dropwhile(predicate, iter): inverse of takewhile

Combinations

For some use-cases (when creating unit-testing during an internship trying to cover all possible cases, some combinatoric functions where really useful):

- itertools.combinations(iter, n): returns an iterator of all psosible combinations of n elements (order doesn’t matter)

- itertools.permutations(iterable, n): ordre matter (2 different order = 2 possible combinations) For statistics, can be useful to simulate the sample of balls with replacement.

- itertools.combinations_with_replacement(iterable, n)

functools module

- functools.partial(function, *args, **kwargs): create a partial object, (callable object, just like a function) which when called will behave like the function in parameter, with positional and keyword arguments passed in. VERY USEFUL:

- functools.reduce(function, sequence, [initial_value]): cumulately perform an operation on each element:

function(function(function(x1, x2), x3), x4))For example for a prod:((x1*x2)*x3)*x4you can provide an initial value (optional) for starting conditions just before x1.

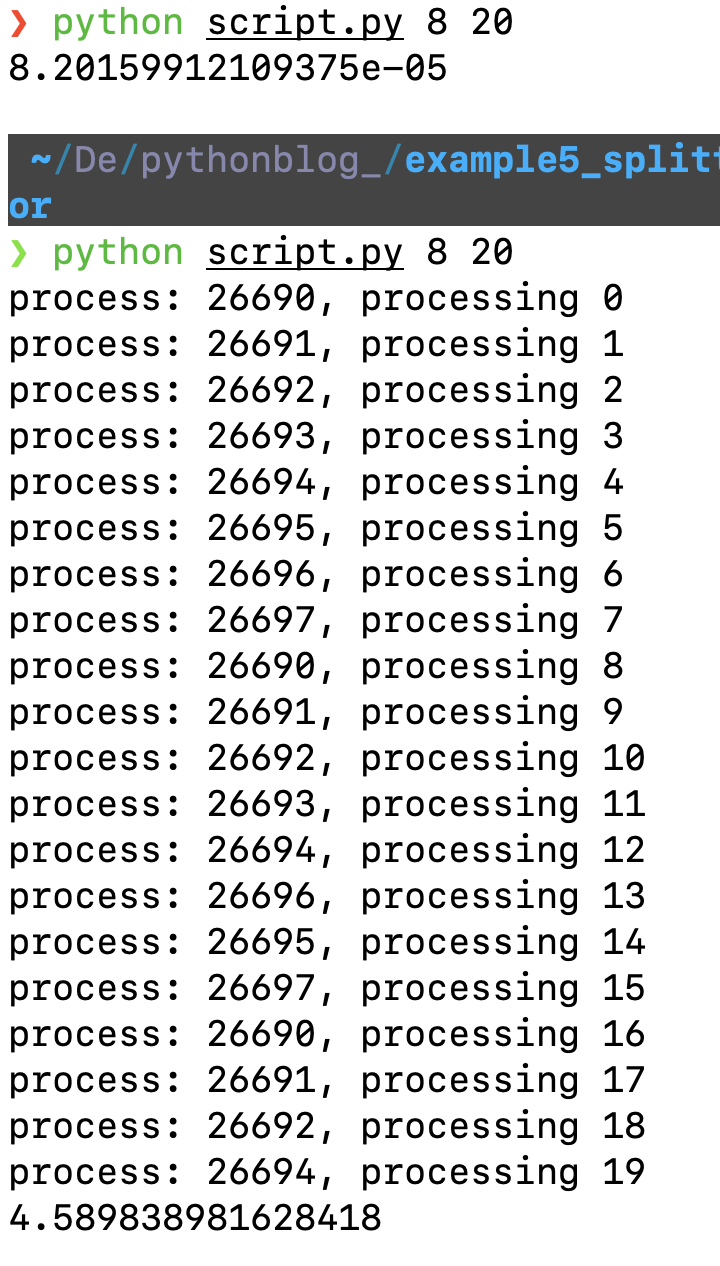

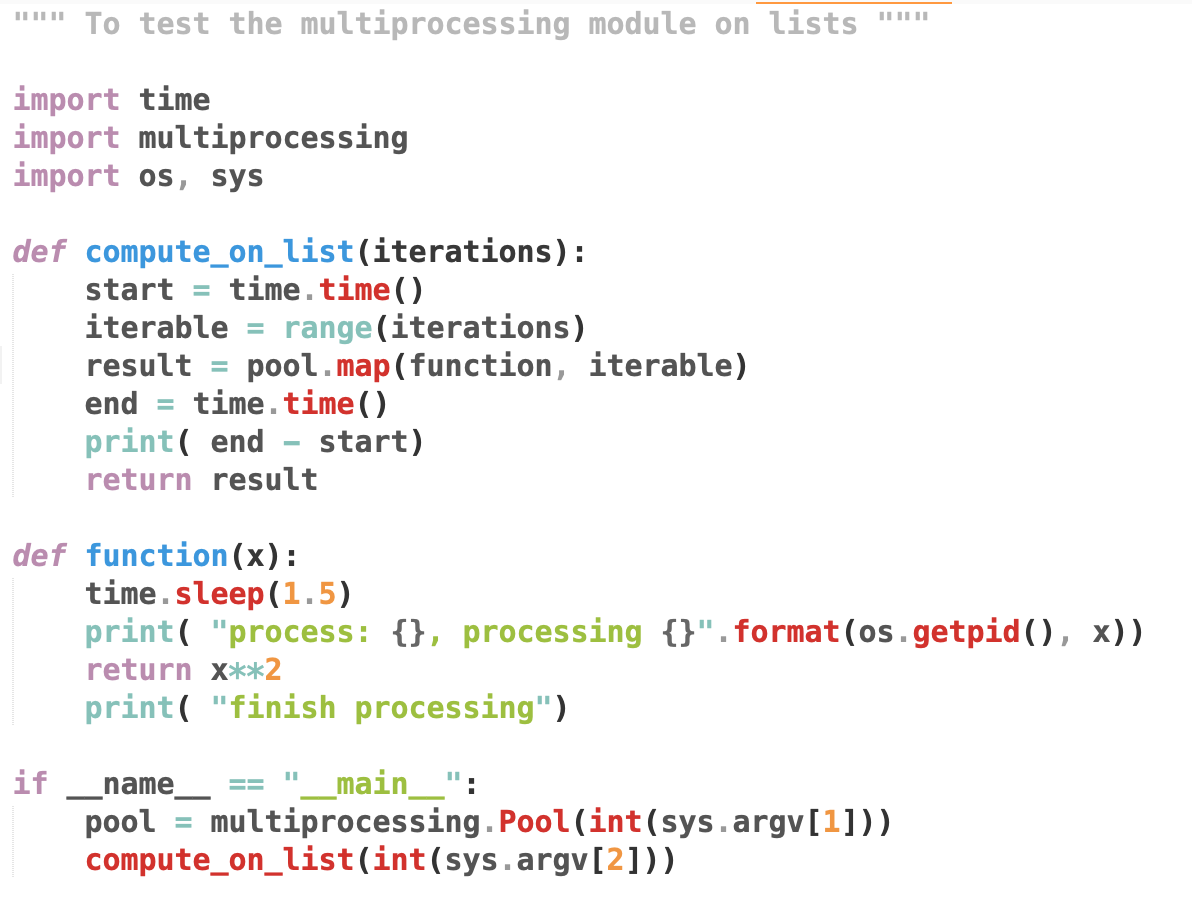

4. What about multiprocessing ?

With reduced memory usage in certain cases, and a evaluation of each item on-demand, iterators/generators are somehow appealing to create pipelines in Data Science for example.

One might want to involve multiprocessing with iterators/generators, by splitting the latter in multiple processes. However, even functions defined within generators/iterators are stateless, the iterator construct is inherently stateful: each item are requested using the next() after one has been consumed already. Splitting a generator into multiple processes would lead to make multiple copies of this generator (one for each process: remember that processes have separate memory). You could still use some techniques but sharing memory should be avoided in general, and in most cases would lead no performance gains from the one expected doing true parallelization.

So where could we leverage multiprocessing while creating some pipelines and making use of iterators/generators?

Well, I see 2 uses cases here, although I’m open to suggestions.

If we have an in-memory stored list and not-so-long, we could use multiprocessing.map to take the list as a whole and split it (or not) in multiple chuncks to be fed to the number of processes in the pool. This could speed up the programm mostly if some heavy CPU-bound computations are being done. The side effect is that multiprocessing.map blocks the calling process until all the processes complete and return the results as a whole.

We could also use multiprocessing.imap to fed sequentially chuncks (or element) to worker processes from a to-long-to-be-stored-iterable and also return lazily an iterable.

I’ve also found a smart implementation using mapalong with itertools.islice, which will still go through the iterator (can’t slice at any place without calling next on preceding elements as iterator are stateful), but has the benefit to be lazy:

pool.imap(function, itertools.islice(iter, N))

here

That’s all for this tutorial, I hope it was informative and concise enough, don’t hesitate to reach me or comment below for any questions.

Go to all course practice sessions !

Go to all course practice sessions !