Flask is a micro web framework written in Python, first released in 2010. It is lightweight (hence the “micro”), has more stars on GitHub that is “concurrent” Django — first released in 2005 — and is based on the philosophy that the main fundations and services are built into Flask and ready-to-use, while additional features can be seamlessly added to your app by installing extensions and initializing them to your app.

2 main dependencies:

- Jinja2, a web templating engine

- Werkzeug, a WSGI library, provides a communication layer between your Python code and a WSGI-compatible server.

Databases, forms validations, user authentification are provided by Flask extensions created by the community.

Setting up the flask project

We need to create a Python virtual environement using venv, which comes in the standard Python library as of Python 3.3.

Installation of flask module:

pip install flask

First app

A client makes a request through an URL endpoint.

An endpoint is specified as a relative or absolute url that usually results in a response from the server.

Upon a request, the server (which can be the built-in WSGI flask dev-server, or a production-grade server such as Gunicorn), which are WSGI compatbile servers, passes this request to the application instance, an object of class/type Flask, which needs to handle it, what code should it run, code embedded within a function for that specific matched endpoint.

This handling function is called a route.

# creation of the application instance (there could be many)

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__) # so flask knows where is the root path of the app

# application instance is called `app`

# those routes are handled by the application instance 'app' (`app` may be imported from a different file or this code could be simply written in the same file after the previous code block)

# endpoint here is the root url '/'

# the decorator turns root_url function to a "route function"

@app.route('/')

def root_url():

# returned value = response

return "<h1>Hello !</h1>"

# endpoint here is '/home/'

# with dynamic url routing

@app.route('/home/<name>/')

def second_url_function_handler():

# name becomes an argument that you can use in the decorated function wrapped by flask decorator

response_string = "<h1>Hello to Home {}!</h1>".format(name)

return response_string

You can access the request object within route functions to get more insight of the incoming request (args, method, json).

This “context glocal” variable is accessible by pushing the request context so Flask knows in which environment/thread/client request he is operating on.

The same way, session object is persistent between requests (can be used to store user informations) and depends on the request context too.

Finally, g and current_app depend on the application context, g is reset between each request and used as storage during handling of requests.

app.url_map shows all the mapped URL endpoint to routes.

Responses:

- returned value(s) from the route as a tuple.

- better:

make_response(data, HTTP_code, [dict_of_header]), you can set additional things using methods of theresponseobject such as setting cookies redirect(url_to_redirect)(flask automatically set the default302HTTP response code used for redirection).

Adding extension(s):

from flask_extension import TheClass

the_instance = TheClass(app) # app instance goes in the constructor of the extension

flask-script: add command-line parser instead of modifying args inapp.run()flask-bootstrap: open source CSS framework from Twitter (also include some js animations)

To connect from another host in the network:

FLASK_ENV=development python ./script.py runserver -h 192.168.0.16

presentation logic: what the user sees and interact with.

business logic: processings invisible to the user.

view functions handle both logics by design, but it is better to allocate presentation logic to the templating engine Jinja to improve readibility and maintainability of the app.

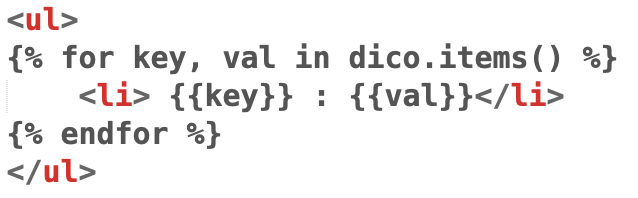

The template is a file that contains the text of the response, with placeholder variables or dynamic parts (loops/conditions) changing from a request to the other. The rendering is the process of associating the computed value from the request to the template placeholders.

Templates are located in “templates” subfolder by default (can be change in Flask constructor)

Then in the view function:

render_template(file.html, key1=val1, key2=val2)

the value could be of any type (dict, list, user-defined objects, etc.)

- filters modify variables in-place {{ variable | filter_name }}

- example1:

capitalizeto capitalize the variable : “luc” -> “Luc” -

example2:

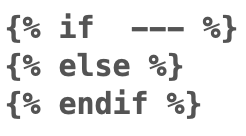

safeto avoid escaping the content of the variable (hence you can put some html tags inside variable it will be rendered as is). Be careful though on security concerns (malicious code that can be inserted into your website). - conditional statements and loops:

- include an html file as is — for example a navigation bar that does not need to be changed — from a template file to another

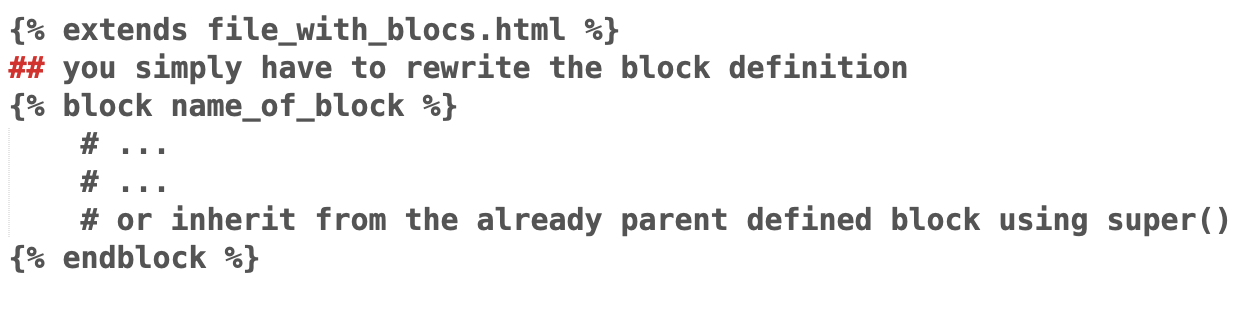

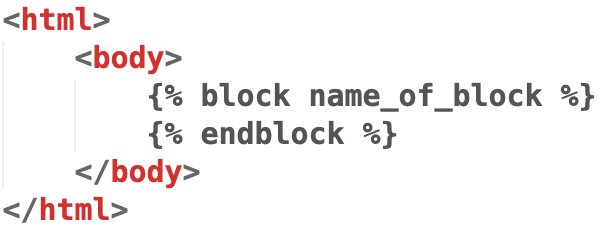

- for portion of html code that need to be modified by a template you can use

and in file_with_blocs.html:

A good practice would be to create different categories of pages with a layout by creating base.html file(s) and derive them for all pages being part of some kind of subcategory. Subcategories can also further be extended:

adding an error handler for a webpage returning some error code

@app.errorhandler(404)

def page_not_found(e):

return render_template('404.html'), 404

This handler function won’t be call unless an Exception is raised, here an HTTPException. Hence we need to import and raises it first:

from werkzeug.exceptions import HTTPException

Then for any endpoint that does not match our previous urls in the url_map, an HTTPException is raised along with the path variable.

@app.route('/<path:nompath>')

def error_test(nompath):

# raises an HTTPException of status code 404

# nompath is the error message

# retrieved from e in page_not_found(e)

abort(404, nompath)

Links should not be hard-coded into the templates folder either.

- to respect the DRY principle (Don’t Repeat Yourself)

- also because it is too complex to write dynamic paths (based on the name provided by a person for example just as for routes handling)

url_for is here for the rescue!, its parameters are the:

- 1st parameter: the name of the routed function

- any number of keyword arguments, each corresponding to a variable part of the URL rule.

_external(Boolean): if evaluated to True, returns the absolute URL, otherwise relative to the root ‘/’.- unrecognized params are appended to the URL as query parameters e.g. test=25 /?test=25

from flask import url_for

Opening the interpreter we can check what url_for could build us:

with app.app_context():

with current_app.test_request_context():

url_for('second_url_function_handler', name="luc")

We obtain ‘/home/luc’ which makes sense with the route logic.

Now we can use it in our template file, for example in the navigation.html

Hence we just linked the route url with the navigation link

But url_for can also be used in the routes handling:

# just as an example

@app.route('/admin/')

def admin():

if not loggedin:

# should login endpoint exist

return redirect(url_for('login'))

And even querying static files (images, assets, CSS) using url_for(‘static’) along with the filename param (e.g. filename='logos/favicon.ico').

Forms

You can access data from POST requests on forms using request.form.

Why using an extension for forms then ?

- For automatic rendering of HTML for the forms (based on a library call WTForms), mainly based on the data type required for each component of the form.

- data validation (critical, before storing in a database for example)

- CSRF protection: to avoid malicious persons making hidden malicious requests from another website visited by a user who is logged-in to the first, and on behalf on him/her (cookies are sent automatically along with the request).

CSRF protection

We first need a key which create encrypted tokens passed along with the form to make sure of user authenticity. the server would generate a random string and add it as an hidden field to the form which is accessible only by the user

app.config["SECRET_KEY"] = "randomly generated string"

A Form Class

To create a form, define a Class “data model”. Each class attribute = a field Each field can have multiple validations hence validators with it. 1st argument is the label of the field, visible to the user.

from wtforms import Form, StringField, SubmitField, IntegerField

from wtforms.validators import DataRequired, Length

class MyForm(Form):

name = StringField("Name", validators=[DataRequired()])

age = IntegerField("Age", validators=[Length(min=13,max=19), Required()])

submit = SubmitField("Submit")

Here is a list of built-in validators provided by the extension. You can also build your custom validators by creating callable classes

After that, you can simply import functions for WTF forms rendering using Bootstrap and call wtf.quick_form() directly on the MyForm object instance.

To pass the form object, we need to change a bit the index function, corresponding to the url endpoint hit by the client where the form will be visible.

from Miguel Grinberg’s book:

Adding POST to the method list is necessary because form submissions are much more conveniently handled as POST requests. It is possible to submit a form as a GET request, but as GET requests have no body, the data is appended to the URL as a query string and becomes visible in the browser’s address bar. For this and several other reasons, form submissions are almost universally done as POST requests.

instance_Form.validate_on_submit(): True if form submitted and data valid.

When a browser is refresh, the last request is submitted again, which is a form submission, leading to a warning by the browser of a double submit. To counteract this we have to do redirect HTTP get request back to the form or in another endpoint/place.

But then, after an HTTP redirect, we don’t have memory anymmore of the values submitted by the user, we then use the request-context global variable sessionfor memorizing informations among different requests.

From pythonise.com Sessions in Flask are a way to store information about a specific user from one request to the next. They work by storing a cryptographically signed cookie on the users browser and decoding it on every request.

You can set the datetime.delta for when the session should be erased. They expire if the user close the browser, unless we specify:

flask sessions expire once you close the browser, unless modify the permanent attribute and set a timeout for expiration.

session.permanent = True

app.permanent_session_lifetime = timedelta(minutes=30) # lasts 30 minutes

Those line can be encapsulated within a request hook i.e. :

@app.before_first_request

def permanent_session():

...

# here

...

You can also play with those items to set a short timedelta value within a before_request hook. Hence an short inactivity would lead to the user being kicked out of the website.

Databases

We will use the ORM SQLAlchemy using the extension Flask-SQLAlchemy.

ORM is short for Object-relational mapper.

It is an higher level of abstraction that enables you to define the data model for your website using Python classes. One class for each table, each class attribute for a field, in an analogous way when we created forms using Flask WTForms.

The main advantage of doing so is mainly because it makes it a very easy-to-use and highly portable solution, since you can sometimes use the same classes for different databases engine (SQLAlchemy will take care of converting those Python representations of the data model into a set of SQL instructions for the proper database engine to create the corresponding table(s)).

pip install flask-sqlalchemy

We now have to create a new entry in the flask app.config object to incorporate the URI location for the database engine (i.e. “where can i locate the database”).

# we will use here the SQLite as it is stored in a disk in the computer rather that relying on another server hosting the database service (either on the same computer or outside).

# absolute path of the directory containing this file

basedir = os.path.abspath(os.path.dirname(__file__))

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI"] = 'sqlite:///' + os.path.join(basedir, 'data.sqlite')

Here are the defined models.

1 User can have multiple Posts

1 Post have 1 User only

Hence Post is the thinnest degree of granularity if we where to join those 2 tables.

It has a foreign key of user representing the user.id_ values.

And a relationship is created on the User model with respect to Post to make SQLAlchemy understand the relationship, giving meanwhile a backref for how to refer to a user instance from a post level.

### models ####

class Post(db.Model):

__tablename__ = "posts"

id_ = db.Column(db.Integer, primary_key=True)

name = db.Column(db.String(64), unique=True)

# 1 User can have multiple Posts.

# Hence we need to put a foreignkey on the Posts,

# where the level of granularity is the thinnest

# (idpost1-user1, idpost2, user1, etc.)

user_id = db.Column(db.Integer, db.ForeignKey("users.id_")) # the ids in this column match with the ids column in user.

# and a relationship in the "Parent" to link them.

def __repr__(self):

return "Post: {}: name {}".format(self.id_, self.name)

class User(db.Model):

# renaming the table and not default user

__tablename__ = "users"

id_ = db.Column(db.Integer, primary_key=True)

username = db.Column(db.String(64), unique=True, index=True)

# this is how SQLAlchemy understand there is a relationship with the model Post

posts = db.relationship("Post", backref="user")

# posts will show a list of related post to one user

# from post, you can access to the user as an object using the backref instead of the "user" foreign_key (which returns only the user id)

def __repr__(self):

return "User {}: with name: {}".format(self.id_, self.username)

###############

using uselist=False (in the db.relationship()) lead to a one-to-one relationship instead of one-to-many relationship.

To create the tables from the models we can interactively open a python interpreter using:

python script.py shell

and instruct:

from script import db

db.create_all()

A new data.sqlite file is created (using the URI defined in the app.config).

As highlighted by Miguel Grinberg, db.create_all() does not update on models changes in the code. Hence a base solution (not the best, especially if your website run and you want to migrate smoothly without loosing your data) is to do a:

db.drop_all()

db.create_all()

note the during the db.drop_all() process, only the tables are being deleted/dropped, not the database-file itself (same for db.create_all() if a database-file at the URI does already exist).

Below is a cope snipped to play with the database, create new entries, set them, filter some

python script.py shell

from script import db

from script import User, Post

db.create_all()

# You can query using the `ModelClass.query`

# From simple query

User.query.all() # all users

Post.query.all() # all posts

# You can insert new elements / rows by first creating the higher-level Python instances

user1 = User(username = "David")

user2 = User(username = "Corentin")

user3 = User(username = "Joséphine")

post1 = Post(name = "Le savoir-faire", user = user1)

post2 = Post(name = "L'étrange Noël", user = user1)

post3 = Post(name = "coder en Python", user = user2)

# Using a dict and unpacking it inside the function signature

post4_dict = { "name": "coder en C", "user": user2 }

post4 = Post( **post4_dict )

# SQLAlchemy will take care of assigning a primary key id_ when writing into the database

# print(user1.id_) output None so far

# add the changes to be made

db.session.add(user1)

db.session.add(user2)

db.session.add(user3)

db.session.add(post1)

db.session.add_all( [ post2, post3, post4 ])

# write the changes to the database

# “All-or-nothing”, if any error occurs, the previous state is unchanged.

db.session.commit()

# Querying again

User.query.all() # all users

Post.query.all() # all posts

# To more advanced ones

# We define a query object

one_query = Post.query.filter_by(name="Le savoir-faire")

# We execute the query using `all()`

one_query.all()

# Some other examples

Post.query.filter_by(user=user1).all()

# the equivalent using `filter`

Post.query.filter(Post.user == user1).all()

Post.query.filter(Post.user.has(username="David")).all()

# we can also use other type of operators

Post.query.group_by(Post.name).all()

executed_query = Post.query.group_by(Post.name).all()

one_post = executed_query[0]

one_post.user

executed_query = User.query.filter_by(username="David").all()

executed_query[0].posts

# when using `posts` from the db.relationship, a query is issued but it returns here a list, no longer queryable, we would want to query the objects it could contain. This can be circumvented using `lazy = 'dynamic’` in `db.relationship` so query is not issued too soon

Migrations

Dropping and recreating all the tables in the database each time the data model change a little bit is really neither convenient nor easy to maintain, even more in the situation where your application is already deployed and registering user or user’s data that you don’t want to be lost.

Alembic is a tool which checks changes in your data model and creates migrations scripts for SQLAlchemy database migrations. Each script contains 2 Python functions (upgrade and downgrade) which can be invoked directly by command-line using Flask-Migrate extensions, so to perform changes on the database level. upgrade() applies the new changes while downgrade() does the exact inverse, allowing you to go to any structures your tables had at a certain timepoint.

Installation of Flask-Migrate:

pip install flask-migrate

Import ad connection to the app:

from flask-migrate import Migrate, MigrateCommand

# adding an handler for web page

migrate = Migrate(app, db)

# to run as command line options using Flask Script

manager.add_command('db', MigrateCommand)

Creation of the migration folder:

python script.py db init

Creation of the first script (from nothing to actual table structure):

python script.py db migrate -m "first migration"

You can known check the scripts in the migration folder which should look like that:

def upgrade():

# ### commands auto generated by Alembic - please adjust! ###

op.create_table('users',

sa.Column('id_', sa.Integer(), nullable=False),

sa.Column('username', sa.String(length=64), nullable=True),

sa.PrimaryKeyConstraint('id_')

)

op.create_index(op.f('ix_users_username'), 'users', ['username'], unique=True)

op.create_table('posts',

sa.Column('id_', sa.Integer(), nullable=False),

sa.Column('name', sa.String(length=64), nullable=True),

sa.Column('user_id', sa.Integer(), nullable=True),

sa.ForeignKeyConstraint(['user_id'], ['users.id_'], ),

sa.PrimaryKeyConstraint('id_'),

sa.UniqueConstraint('name')

)

# ### end Alembic commands ###

def downgrade():

# ### commands auto generated by Alembic - please adjust! ###

op.drop_table('posts')

op.drop_index(op.f('ix_users_username'), table_name='users')

op.drop_table('users')

# ### end Alembic commands ###

This is the same as creating the tables the first time. After that, any new changes in the model and any new migrations scripts derived from them will be incremental changes from the current model.

The script isn’t applied yet, it was here for review.

To apply it (and in that case actually create the 2 tables along with their data attributes), let’s run upgrade()

python script.py db upgrade

output:

INFO [alembic.runtime.migration] Running upgrade -> 3dc85275c029, first migration

You can finally:

- create a GitHub repository

- create a

.gitignorefile (to exclude including unecessarymyenvvirtual environment) - create a

requirements.txtfile where all files will be - create a

READMe.mdmarkdown file for the users who will go to this GitHub repository

A note on execution model

A note on execution model